Leonardo da Vinci designed a sophisticated robot to mimic the motions of an armored knight. Could this Renaissance man’s creation work today?

A computer in downtown Manhattan is displaying a robotics designer’s latest creation in action. Fashioned to look like an armored knight, the mechanical man in this three-dimensional simulation sits up, waves its arms, moves its head on a flexible neck, and opens and closes its hands and its jaw, all in smooth, precise motions. An inside view of the machine reveals a complex system of cables and gears. The robot could be used in a new motion picture, museum, or amusement park. Its original designer, however, never heard of movies, computers, or Walt Disney: The robot sprang from the mind of Leonardo da Vinci.

The computer model made its public debut recently with the New York stop of “Mechanical Marvels: Invention in the Age of Leonardo,” an exhibition on an international tour. In the Liberty Street Gallery of the World Financial Center, the designs for the automaton appear alongside another imitation of nature, Leonardo’s flying machine. While the latter device is more well known, the robot is no less impressive in its inner workings and its approach toward mechanical engineering.

This “anthrobot” — a robot that mimics the human body and its motions — would seem to be a logical result of Leonardo’s wide-ranging studies during the Renaissance not only of mechanics but also of human anatomy and kinesiology, yet the design was overlooked for centuries. In the 1950s, Carlo Pedretti, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, proposed that certain drawings in Leonardo’s notebooks were actually plans for a robot. Four decades later, Mark Rossheim, president of the Minneapolis-based robotics-design firm Ross-Hime Designs, examined these and other drawings further, and recognized the components of a cable-transmission system that could automatically control the movement of articulated limbs.

Rossheim then worked with the Institute and Museum of the History of Science in Florence, Italy, to create computer models to determine whether Leonardo’s sketches could work. The simulations “made clear that these were drawings fir a mechanical man, able to make a series of motions,” said exhibit curator Paolo Galluzzi, director of the institute and museum.

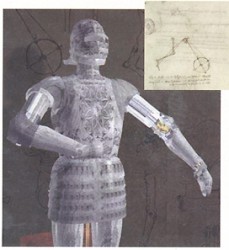

Leonardo planned out the inner workings for a robot — including the drivetrain for the device’s legs (inset) — that were found in many of his notebooks. More than 400 years later, designers gathered these “napkin sketches” to create computer models of this mechanical man, clad in a suit of German-Italian armor of the Renaissance era, to determine whether such a device would actually work.

According to Galluzzi, the robot was designed around 1495 — before Leonardo began painting The Last Supper — probably for a theatrical festival in Milan, Italy. These festivals “were common at the end of the 15th century, with special effects such as moving mountains or flying people,” he said. For such a spectacle of mechanical motion, the robot would have been dressed in a German-Italian suit or armor typical of the period and crafted from wood, leather, and brass or bronze. The warrior may also have generated its own automated drum music during its “dance.”

Proportions of Man was one of many studies of the human body by Leonardo da Vinci. His research has influenced robotics designs in the 15th and 20th centuries.

“The design was very ingenious,” Rossheim said, ” so much so that at first the pulley system [Leonardo used] wasn’t obvious to me.” The robot consisted of two independent systems: three-degree-of-freedom legs, ankles, knees, and hips; and four-degree-of-freedom arms with articulated shoulders, elbows, wrists, and hands. The arms were positioned so they could perform whole-arm grasping, which means all the joints moved in unison. Within the torso of the robot was a mechanical, analog-programmable controller, which incorporated a rotating cylindrical, grooved cam. This cam triggered high-torque worm gears, attached to a central pulley, to drive the arms.

The prime mover of the robot could have been a falling weight or a water wheel hidden in a separate room. In either case, power for the entire device was transferred to a central shaft, perhaps splined, that also enabled the robot to stand and sit in a straight vertical motion. The external crank arrangement helped drive the legs, and was connected to key locations in the ankle, knee, and hip.

Many elements of this machine would most likely not be found in modern robots — pulleys, for example, drove Leonardo’s invention, while today more-complex actuators would be located next to each “muscle” of an anthrobot — but the design is very contemporary, according to Rossheim. “Designers are still very much into designing cable-operated robots, such as for medical and nuclear robots,” he said. “Also, cams are still used to drive today’s simple robots.”

The designs — which Rossheim called the equivalent of current-day “napkin sketches” — and the 3-D simulation show the robot to be very feasible. Leonardo experts, however, can only theorize for now that the device was actually built. “The finished robot drawings were plundered at some point in time,” Rossheim said, and remain among approximately 14,000 missing pages of Leonardo’s work. …

Portfolio(s): Editorial

Project type: Writing and Reporting

Posted: February 1998